For one week, from March 26, 2015 until April 2, 2015, Indiana found itself a battlefield in the nationwide culture war. Below is my perspective on the “Battle of the Indiana RFRA” from my vantage point on the front lines.

For one week, from March 26, 2015 until April 2, 2015, Indiana found itself a battlefield in the nationwide culture war. Below is my perspective on the “Battle of the Indiana RFRA” from my vantage point on the front lines.

The origin of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act dates back 25 years to a 1990 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Employment Division vs. Smith. Two Native Americans in Oregon were fired from their jobs and denied unemployment compensation because they used the illegal drug peyote as a part of a religious ceremony. The employees tried to use the First Amendment’s free exercise of religion clause as a defense. SCOTUS ruled against them, declaring it was not necessary for the state’s drug laws to make an exception for acts done in pursuit of religious beliefs.

Congress was not a fan of this decision. In reaction, they passed the original RFRA in 1993. The law (42 USC 21B) states that the government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion unless the burden is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and the burden is the least restrictive means of furthering that interest. The law was introduced by then Rep. Chuck Schumer in the House, carried by Sen. Edward Kennedy in the Senate, passed nearly unanimously, and signed by President Bill Clinton.

In 1997, SCOTUS ruled in City of Boerne v. Flores that RFRA only applied to federal law and not state and local laws. As a result, twenty states passed their own version of RFRA, including Illinois, which passed RFRA in 1998 with the support of then State Senator Barack Obama. (Some have excused this vote by pointing out that Illinois also has an LGBT anti-discrimination law. They neglect to mention that the anti-discrimination legislation wasn’t passed until 2005.)

So what changed? Why would language that Democrats lauded only a generation ago now be vilified by those same individuals as bigoted? Obviously it’s because of a cultural shift in attitudes toward same-sex relationships. Traditional marriage advocates in Indiana tried to push back against this shift with the initial passage of a state constitutional amendment defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman, as was already defined in Indiana statute, in February 2014. Full adoption would have required a second passage by subsequent legislature and approval by a voter referendum.

It didn’t take long for that to become a moot exercise. The following month, three lesbian couples from Indiana filed a lawsuit, Baskin v. Bogan, in federal court for the ability to marry. In June, the district court ruled for the plaintiffs, finding their rights to due process and equal protection of law under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution were being violated. In September, the circuit appeals court upheld the decision, and then in October, the U.S. Supreme Court let stand those rulings. Just like that, Indiana’s law was overturned and Hoosier gay couples could marry.

Which brings us to 2015. Now that same-sex marriage was legal in Indiana, attention turned to protecting those who did not believe in gay unions. Some legislators were concerned about events that had taken place in other states regarding the issue. In Houston, the mayor had subpoenaed sermons that area pastors had given regarding homosexuality. An Oregon bakery was ordered to pay $135,000 to a lesbian couple for refusing to make them a wedding cake. A florist in Washington was directed by a judge to provide flowers for gay wedding ceremonies.

The mechanism chosen to prevent such incidents from happening here was RFRA, which was top of mind after another SCOTUS case in 2014, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, where the court decided that because of the federal RFRA, a privately held company could not be forced by the government to include coverage for abortion-inducing contraceptive drugs as a part of the health insurance provided to its employees.

When the bill was debated in Indiana, the discussion did not center on homosexuality. Examples that were cited in which the law would apply included a Muslim prisoner in Arkansas who was allowed to grow a beard contrary to Department of Correction policy and the Amish buggy drivers in Kentucky who resisted laws requiring them to place an orange triangle on the back of their vehicles and won the right to use reflective tape instead. The focus was on restricting Indiana state and local governments from infringing on the religious beliefs of individuals or businesses.

But what about disputes between two individuals or businesses? Different federal circuit courts, as well as courts in the other states who had already adopted RFRA laws, had come to different conclusions as to whether RFRA would apply to civil lawsuits. To avoid confusion, legislators amended the bill to clarify that RFRA could be asserted as a defense in a civil case, regardless of whether the state or a local government was part of the lawsuit.

I should emphasize that RFRA has never provided blanket immunity to those sued for discrimination. It simply allows for the defendant to raise religious objections as a defense. It would still be up to a judge to decide, according to the facts of the case, whether those religious objections are overridden by a compelling state interest in the least restrictive means possible.

This lack of clarity on the scope of RFRA’s applicability in discrimination cases was the source of its controversy. The bill’s proponents were motivated by a very narrow instance of a defendant (e.g., minister, florist, baker, photographer, etc.) asked to participate in a religious sacrament. Opponents of the bill feared a much broader application, such as companies refusing to hire gay workers, restaurants turning away gay customers, or landlords rejecting gay tenants.

Let me reiterate that prior to the bill’s passage, there was no outrage expressed about wider discrimination against gays and lesbians. It was not until after the bill became law the organized attacks began. To clarify, I do not doubt the sincerity of gays who were afraid they could be kicked out of a restaurant because of RFRA. Yet, I do believe that activists fostered these fears for political ends. These activists also used Saul Alinsky-type tactics to intimidate legislators. For instance, customers of the family business owned by one of the bill’s authors were threatened with boycotts if they did not sever ties his company.

After the bill was signed, Governor Mike Pence appeared on This Week with George Stephanopoulos. Stephanopoulos repeatedly asked the governor whether Indiana’s RFRA legalized discrimination against gays. When the governor declined to answer the question, it appeared that he was confirming opponents’ concerns that the law sanctioned broader discrimination. What he should have done is acknowledged that under very restricted circumstances, such as when a wedding service provider had religious objections to participate in a gay wedding, he hoped that a judge would not compel the business or person to do so.

Of course, all of that is Monday morning quarterbacking. In retrospect, there may have been nothing Governor Pence could have done to halt the avalanche of negative attention on Indiana. A false narrative had taken hold, “Indiana RFRA legalizes discrimination,” and with the help of social media, that false narrative had gone viral. It was frustrating that the perception of what the law did was the news story, not what the law actually did. Like it or not, perception had become reality.

Another thing which became very real was the adverse economic impact the controversy had on the state, and Indianapolis in particular, which is heavily dependent upon visitors to the area. Within only a few days, a billion dollars’ worth of convention business was cancelled and more losses were threatened. Furthermore, the lost economic activity meant less revenue available for schools, roads, public safety, and the like.

And so, a follow-up bill was crafted to limit RFRA’s applicability in discrimination cases. Only a church or religious organization and its minister/priest/rabbi could use it as a defense. That is not where I would have drawn the line, but there was no opportunity to change it. I did not relish voting for a bill negotiated with corporate leaders behind closed doors, but given that there was an economic gun pointed at Indiana’s head, there was little choice.

After SCOTUS’s Obergefell v. Hodges decision a few months later, same-sex marriage is now the law in all fifty states. Just as Roe v. Wade did not end the acrimony over abortion, we will be arguing over gay marriage for quite some time. As Indiana’s experience shows, the right to marry is not enough for some gay rights advocates. They want the government to force all service providers to participate in a gay wedding, despite the plethora of businesses willing to do so. (See last week’s ruling against a Colorado baker.)

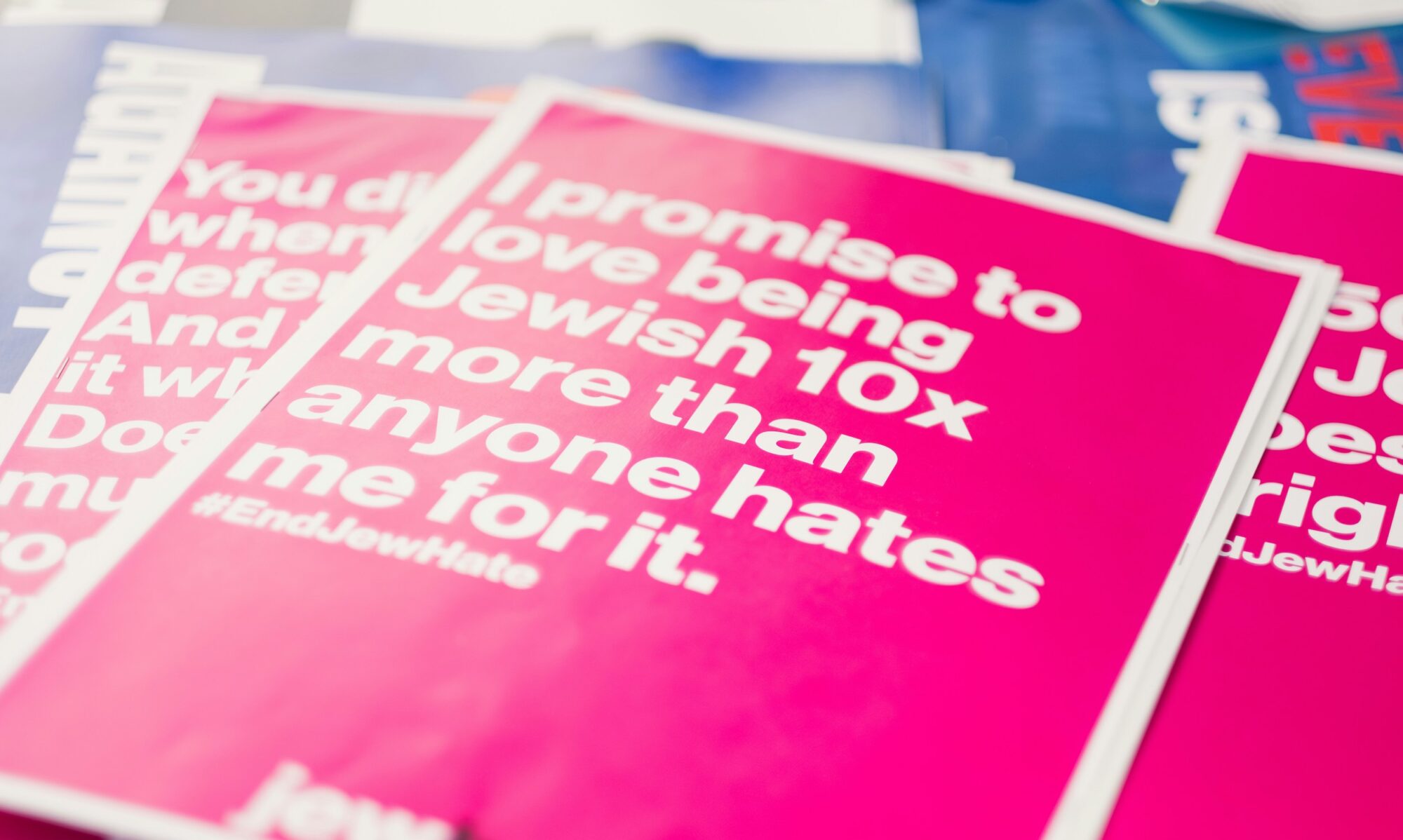

What we should do instead is develop a “live and let live” legal framework. If a gay person owned a print shop and a prospective customer ordered 100 signs that said “Homosexuality is a sin,” should the owner be within his rights to refuse the business? Of course, he should. Why should the Christian wedding service provider not have the same right?

How we answer that question is the next battle in the culture war.

Respectfully…

Pete

Infornative and insightful! Thanks.